|

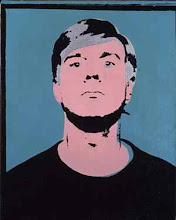

| Käthe Kollwitz, Self Portrait, 1904 |

Portrait of the Artist: Käthe Kollwitz is at

Ikon until 26 November 2017.

In his succinct and moving account of Käthe Kollwitz’s life

and work, Neil McGregor makes a persuasive case for her being one of the ‘greatest

German artists’. (

Listen here.)

Kollwitz worked, principally, as a printmaker and took social

injustice, pain and suffering as her overriding themes. Her compassionate

approach achieves work of considerable pathos – evident, for example, in

Woman with Dead Child, 1903. The model for the child was her own son, Peter. As

McGregor points out, this proved to be tragically prophetic: his discussion

focuses on her sculpture

Mother with Her Dead

Son, which is in the

Neue Wache (New Guardhouse) on Unter den Linden in

Berlin, where it serves as a memorial to ‘victims of war and dictatorship’. (See

image at bottom of page.) The sculpture was her own memorial to Peter. The

story is that at 18, in 1914 at the outbreak of the first World War, Peter wished

to volunteer for military service but, being under 21, could only do so with

parental consent. Peter’s father at first refused but was persuaded to relent

by Käthe. Peter was killed in action a mere 10 days after joining up. Grief,

guilt and a fervent pacifism marked the rest of Kollwitz’s life. She died in

1945.

Although her work may seem unrelenting in its representation

of pain and suffering, it is also beautiful and, I think, unsentimental in its

honesty. This exhibition mostly drawn from the print collection of the British

Museum is a rare opportunity to see work by this major artist.

|

| Käthe Kollwitz, Woman with Dead Child, 1903 |

|

| Käthe Kollwitz, Not (Want), 1893-7 |

|

| Käthe Kollwitz, Bust of a Working Woman With Blue Shaw, 1903 |

|

Käthe Kollwitz, Death and Woman, 1910

|

|

| Käthe Kollwitz, Self Portrait, 1924 |

|

| Käthe Kollwitz, Self Portrait, 1924 |

|

Käthe Kollwitz, Mother with her Dead Son in the Neue Wache, Berlin

|

|

| Käthe Kollwitz, Mother with her Dead Son in the Neue Wache, Berlin |