|

|

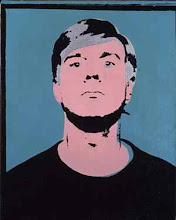

Allan Sekula and Noël Burch, still from

The Forgotten Space, 2010

|

Allan Sekula died on 10 August 2013.

Photographer and filmmaker, Allan Sekula practiced a form of

critical realism. His work was marked by a consistent preoccupation with politics

and economics and a firm commitment to a practice with a socially critical

purpose: he saw photography as having a “special aptitude for depicting

economic life, for what used to be called ‘documentary’, and for an affinity

between documentary and democracy.”

He cared nothing for the debates about

photography’s status as art but was clear sighted about the ‘art world’ which

he described as:

“a small sector of culture in general, but an important one.

It is, among other things, the illuminated luxury-goods tip of the commodity

iceberg. The art world is the most complicit fabrication workshop for the

compensatory dreams of financial elites who have nothing else to dream about

but a ‘subjectivity' they have successfully killed within themselves."

Significant works include Untitled Slide Sequence (1972), Fish

Story (1988-94) and (with Noël Burch) The

Forgotten Space (2010).

|

| Allan Sekula, Untitled Slide Sequence, 1972 |

Untitled Slide Sequence (1972) could be

seen as a take on both documentary and street photography – but one that is at some distance from

the contemporary work of Winogrand or Friedlander. The

work consists of 25 images of workers leaving the General Dynamics Convair Division aerospace plant at the end of their shift.

The work comprises every shot Sekula took until stopped by company officials. The

images were shown as projected 35mm slides: “The rhythm of the slide projector

is the rhythm of the automated factory, but the individual frame individuates

both the photographer and the subject."

The container box

is the unlikely focus of Fish

Story (1988-94) as well as the film, developed out of that project, The Forgotten Space (2010).

|

|

Allan Sekula, "Doomed

Fishing Village of Ilsan, September 1993", from Fish

Story 1989–95

|

|

|

Allan Sekula, "Welder’s Booth in Bankrupt Todd Shipyard, Two Years After Closing, Los

Angeles Harbor, San Pedro, California. July 1991", from Fish

Story, 1989–95

|

|

|

Allan Sekula, “’Pancake’,

a former shipyard sandblaster, scavenging copper from a waterfront scrapyard,

Los Angeles harbour, Terminal Island, California” from Fish Story, 1989–95

|

As Jennifer Burris notes, the invention of the container in

the 1950s revolutionised shipping and brought profound social and economic

consequences: the rise of the super-ship and the super-port reduced the

required workforce, and the contrivance of registering ships under a ‘flag of

convenience’ allowed a deregulation of international labour markets which

allowed "labour conditions to remain at

standards set in the nineteenth century". Fish Story examines this story in 7 chapters of image and text.

The Forgotten Space

(2010) "showcases the maritime world as

the ultimate ‘forgotten space’ of global capitalism".

|

|

Allan Sekula and Noël Burch, stills from

The Forgotten Space, 2010

|

"The Forgotten Space follows container cargo aboard ships, barges, trains and trucks, listening to workers, engineers, planners, politicians, and those marginalised by the global transport system. We visit displaced farmers and villagers in Holland and Belgium, underpaid truck drivers in Los Angeles, seafarers aboard mega-ships shuttling between Asia and Europe, and factory workers in China, whose low wages are the fragile key to the whole puzzle."

Following his death, Thomas Lawson wrote,

"As a writer,

Allan described with great clarity and passion what photography can, and must

do: document the facts of social relations while opening a more metaphoric

space to allow viewers the idea that things could be different. And as a

photographer he set out to do just that. He laid bare the ugliness of

exploitation, but showed us the beauty of the ordinary; of ordinary, working

people in ordinary, unremarkable places doing ordinary, everyday things. And,

like the rigorous old-style leftist that he was, he infused that beauty with a

deep sense of morality."

See:

Jennifer Burris (2011) "Material Existence: Allan Sekula's Forgotten Space", Afterall

Edward Dimendberg (2005) "Allan Sekula", Bomb

Bill Roberts (2012) "Production in View: Allan Sekula's Fish Story and the Thawing of Postmodernism", Tate Papers, Issue 18

Sukhdev Sandhu (2012) "Allan Sekula: Filming the Forgotten Resistance at Sea", The Guardian