|

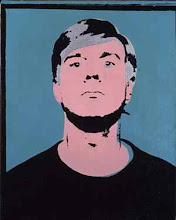

| Sarah Lucas, Fighting Fire with Fire, 1996 |

Performing for the Camera is at Tate Modern until 12 June 2016.

The camera invites

performance: the lens turned towards us compels, at the very least, an

adjustment of expression and gaze. It may be that the camera doesn’t lie – but

we do, when we create these little fictions for photographs. The contemporary

apotheosis of this performance is the selfie where we become director, subject

and audience. (I enjoyed David Bailey’s recent comments on the topic: … somebody said ‘what do you think of

selfies?’... I thought it meant masturbation. And then they told me what it

was, and I realised it is masturbation! – see short video here.)

The publicity for Performing for the Camera, featuring

images by Romain Mader and Amalia Ulman, suggested that it was this

narcissistic trope of the selfie that was the exhibition’s subject (albeit,

that both Mader and Ulman self-consciously construct fictional identities).

|

| Amalia Ulman, from Excellences and Perfections, 2014 |

However,

the exhibition is broader and more interesting than that, taking as its main

focus the documentation of Performance Art as well as performance enacted for

the camera.

The exhibition opens with

Yves Klein’s well-known Leap into the

Void (1960). The photograph shows

Klein in mid-flight from a first floor ledge with, apparently, nothing to prevent

his inevitable fall onto the street below except for, presumably, his faith in

immaterialism and transcendence - and the viewer’s suspension of disbelief. It

is obviously a trick: a composite photograph – but very persuasively done.

Here, however, it is ‘explained’ with the display of the photograph showing

Klein’s friends waiting below with a tarpaulin to catch him. Klein (who died in

1962) was insistent that the trick should not be revealed, so it seems a little

sad that is it so bluntly revealed here. Once the ‘magic’ is explained – it is gone.

Leap

into the Void is

unequivocally Klein’s ‘work’; however, the photograph was made by Harry Skunk

and János Kender; as were the many, many photographs of Klein gleefully

directing his ‘living paintbrushes’ (naked women smeared with blue paint); in

fact, one of the revelations of this exhibition is that the photographs of

Skunk/Kender were key to much Performance Art of the 1960s and 70s – here we

see their work with Niki de Saint

Phalle, Marta Minujín, Eleanor Antin, Yayoi Kusama, Dan Graham and Merce

Cunningham, besides Klein; typically, in such instances, the photographer is

effectively merely a technician in the archival process. Clearly this raises

questions about who the artist is and where the art is – this is intrinsically

problematic with performance given that, in these examples, it only really

exists in the ‘live’ moment; another section of the exhibition looks at

events/performance which is made specifically to be photographed. (Sometimes

the point of the photograph is ambiguous – I looked with pleasure at Babette

Mangolte’s gorgeous, misty rooftop view across New York dominated by that

city’s, characteristic quirky water towers for some time before I realised that

I was supposed to be attending to the individual figures from Trish Brown’s

Dance Company distributed across the roofs.

Much of this exhibition

presents familiar material – given that reproducibility is a defining characteristic

of the medium this is often a potential problem for photography exhibitions:

when work is exhibited as small, framed black and white prints (as much in the

first few rooms, here, is) I can’t help feeling that seeing them in a book (such

as the excellent catalogue) would be more effective; when those pictures are

arranged in rows that begin near to the floor and rise to considerably above

head height (as with the display of Stuart Brisley) it is just irritating.

However, there is work

here that looks fresh and work that is displayed at a quality and scale that makes

the most of gallery presentation.

Work that I particularly

enjoyed included David Wojnarowicz’s series Arthur

Rimbaud in New York; Jemima Stehli’s Strip;

Hans Eijkelboom’s creepy portraits of himself posing with other people’s

families; and Samuel Fosso’s African

Spirits (his self-portraits as Angela Davis, Malcolm X and other

significant figures make a refreshing juxtaposition to Cindy Sherman’s more

familiar Untitled Film Stills.)

I also loved the wall of

Joseph Beuys posters!

Read reviews by AdrianSearle, Waldemar Januszczak, Mark Hudson, Rachel Spence.

(Click on images to enlarge.)

|

| Yves Klein, Leap into the Void, 1960 - photograph by Skunk-Kender |

|

| Yves Klein, Anthropometries of the Blue Period, 1960 - photograph by Skunk-Kender |

|

| Babette Mangolte, Trisha Brown: 'Roof Piece', 1973 |

|

| Hans Eijkelboom, With My Family, 1973 |

|

| David Wojnarowicz, from Arthur Rimbaud in New York, 1978-9 |

|

| Francesca Woodman, Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976 |

|

| Jemima Stehli, from Strip, 1999-2000 |

|

| Samuel Fosso, African Spirits: Angela Davis, 2008 |

|

Joseph Beuys, La Rivoluzione Siamo Noi, 1972

|

%2C%2B1937%2B(2).jpg)

.jpg)

%2C%2B1925%2B(2).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)