|

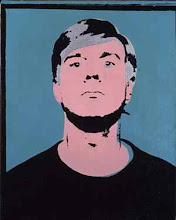

| Bob Davison, Borders, Big Yellow, 2014 |

The following text was written for the catalogue.

About Looking

Borders: outlines and edges, but, also, national boundaries,

flower beds and frames. Borders define areas but also propose the ambiguity of

a place of transition: where precisely are you as you cross the border from one

state to another? Where precisely does the town end and the country begin?

The notion of a borderland is apt for Bob Davison’s art

which occupies the liminal state between figuration and abstraction, mirroring

perceptual processes which integrate objective observation with the

subjectivity and ambiguity of memories and feelings.

The mystery and magic of seeing is that, unlike a camera’s

mechanical recording of data, our vision is constantly informed and coloured by

experience both consciously and unconsciously: what lies beyond the border of

consciousness shapes what lies within; what lies outside our immediate frame of

vison informs what we see inside.

Davison’s subtle and beautiful meditations on nature and

memory, on colour and form, are rich counterpoints to the mechanistic images

which dominate our contemporary culture and ways of seeing. Pictures are

everywhere. In 1964 Susan Sontag wrote Ours is a

culture based on excess, on overproduction [1]; half a

century on, our visual culture is super-saturated with images. The camera has a

lot to answer for. |

| Bob Davison, Dappled, Big Red, 2015 |

The gifts of photography to knowledge – and to art – have been

prodigious. But photography has spoiled us, too. We have been spoiled, not just

by the superfluity of images - Is there any thing, any place, that has not yet

been photographed, that we cannot ‘see’ and know through this extraordinary

medium? - but it has also spoiled us in the very act of perception.

Lee Friedlander, wanting a snapshot of his uncle with his new car noted

that, I got him and the car. I also got a bit of Aunt Mary’s laundry

and Beau Jack, the dog, peeing on a fence, and a row of potted tuberous

begonias on the porch and seventy-eight trees and a million pebbles in the

driveway and more. It’s a generous medium, photography.[2]

Generous to a fault. The camera’s gaze reveals everything in

fascinating, but superficial, detail. Human perception might seem a poor

thing next to the revelatory detail furnished in a high definition, colour

saturated, digital image, showing us all the visual information we would

otherwise have overlooked – and, perhaps, it has made us lazy; in Sontag’s

view, the result is a steady loss of sharpness in

our sensory experience [3]. We see

only the surface appearance; we need to look harder.

Which is where drawing and painting comes in. Bob Davison’s pictures

offer rich pleasures and demand prolonged looking: they embody the recognition

that the fullest experience of the world is dependent not on mere knowledge and

information (both in overwhelmingly plentiful supply in our digital world) but

on looking, thinking, acting and feeling. (John Constable declared painting is… feeling [4]).

Visual perception is more than data collection: it is informed by

movement and emotion, memories and imagination. The human eye is never

still; it is constantly scanning and calculating, discriminating and selecting.

We experience the world by moving through it. We see what is interesting and

important to us – what is meaningful. These sights and the accompanying sensations

and emotions are stored away as memories – imperfectly, perhaps – to inform subsequent

perceptions. |

| Bob Davison, Petiolaris, 2013 |

Remembering a selection of Davison’s paintings and drawings

seen during a recent visit to his studio, I remember, in particular, a

scattering of bright yellow flowers (Welsh poppies, perhaps?) a swathe of

curious, white oblong forms rhythmically dispersed across the canvas (sometimes

suggestive of blossom, sometimes of patterns of light), the elegant silhouettes

of complex plant forms.

When I return to look again I find that (of course) my

recollections are inadequate. The richness, complexity and subtle layering of

Davison’s work mean that – unlike ‘reading’ a photograph which can deliver a

great deal of information very quickly (and need not detain the viewer for very

long) – the paintings demand, and repay, prolonged scrutiny and even then do

not exhaust their visual pleasures, for each further viewing will reveal fresh

colours, forms and textures. |

| Bob Davison, Umbellifers, 2014 |

The achievement of these paintings is hard won: Davison’s

study of nature and art has been intense, resulting in his mastery both of

drawing from nature and of the language of painting. The story of modern

painting has broadly been a dance (sometimes a battle) between figuration and

abstraction – for a while total abstraction was the dominant mode (and

Davison’s early work shows his mastery of a minimalist style) but, today, a

fruitful dialogue (cross-border discussion) is possible, and Davison’s work is

exemplary in this respect. As flowers

dance in a breeze, so shapes and forms in the paintings dance between figure

and abstraction: forms dissolve and reform in the ambiguous, translucent space

of shadows and reflections. It is a mark of great painting that form and

content are, as here, inseparable from each other.

To return, finally, to Susan Sontag’s reflections on modern

visual culture: her prescription to counter what she sees as the dulling effect

of our over exposure to images is simple: What is

important now is to recover our senses. We must learn to see more, to hear

more, to feel more [5].

The gift of Bob Davison’s luminous paintings is precisely to reward

the act of looking with an apprehension of the beauty and mystery of the world

before us: to cross the border between appearance and sensation, between

looking and feeling.

Richard Salkeld, 2016.

[1] Susan Sontag (2009) Against Interpretation and Other Essays, London: Penguin, p13

[2] Galassi, Peter (2005) Friedlander, NY: The Museum of Modern Art, New York, p14

[3] Susan Sontag, ibid., p13

[4] Stephen F. Eisenman (2011) Nineteenth Century Art, London: Thanes & Hudson, p232

[5] Susan Sontag, ibid., p14