|

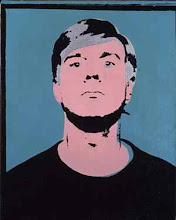

| Claude Monet, The Japanese Bridge, c1923-5 |

(The following review is published in Landscape Issues, Vol.15, Nos.1 & 2, May 2016)

Claude

Monet is undoubtedly the star of this huge show – supported by a cast of some

40 other painters. Although the exhibition title signals a historical span

bookended by Monet and Matisse, it is notable that the later giant of Modern

art is represented by a paltry two paintings to Monet’s 35 or so.

It is,

nevertheless, quite fitting that this should be so: given the premise of the

exhibition, that many pioneers of modern painting were enthusiastic gardeners,

and engaged in a productive dialogue between the possibilities of horticulture

and painting, Monet is in a league of his own. Not only did his garden at

Giverny become the exclusive subject of his painting, but the garden itself was

a work of art. Monet was no mere Sunday-gardener, he was nothing less than a

landscape architect. Over a period of 40 years, from 1890, he developed and

extended a country garden into a 6-acre composition of foliage and flowers;

eventually he was able to employ 6 gardeners and divert a local river to create

the famous water garden with its iconic Japanese bridge. Monet declared that

his garden was his studio.

The

period spanned by the exhibition – roughly 1864 to 1928 – was, art

historically, one of extraordinary invention and experiment. Modernism was

forged in wave after wave of avant-gardism: Impressionism, Post-Impressionism,

Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, Dada, Surrealism. Broadly, this is a story of

escalating ‘difficulty’ in painting – difficulty for the viewer, that is, as

what was seen in paintings became increasingly disconnected from what could be

seen in the natural world and increasingly engaged with psychology, abstraction

and provocation, to say nothing of revolutionary politics.

Understandably,

there is little of that revolutionary ilk here – the section rather cornily

labelled ‘avant-gardeners’ does present some of the major figures of that extraordinary

period – Van Gogh, Klimt, Klee, Kandinsky, Nolde, Matisse – but, Nolde and

Klimt, aside this fairly tame section feels like a distraction from the main

business of supplying visual pleasure and, in particular, the pleasure of

flowers.

The

overriding aesthetic ethos of this exhibition is Impressionism. It is hard, now,

to believe that Impressionism was ever shocking. Impressionism may have

initially, and briefly, provoked a negative response – to a public and to critics

weaned on polished, academic pictures, the brushy smudges of pure colour seemed

unfinished and hard to ‘read’ – but, eventually, once the idea of a spontaneous

response to the play of light on the natural world was grasped, the movement

became, and remains, immensely popular. While more radical avant-gardism was

intent on épater les bourgeois the Impressionists forged an art that was

bourgeois to its core, intent principally on visual pleasure. Impressionism

combined here with gardening is a cast-iron crowd pleaser.

The

exhibition is, indeed, rich in visual pleasure for both the connoisseurs of

painting and of horticulture – though, perhaps, less reliably so for the

latter. The joy of Impressionism is that the painters played fast and loose

with the visual sensations offered by the sunlit scenes before them so that flowers

become sensuous smears of red, orange, white and blue rather than botanically

accurate representations.

Overall,

I think there is more to be learned here about the development of modern

painting than about the ‘modern garden’ of the title. Highlights include

marvellously ethereal paintings by Berthe Morisot (Woman and Child in a Meadow,

1882) and Edouard Manet (Young Woman among Flowers, 1879); Max Liebermann’s Flowering

Bushes by the Garden Shed, 1928, rendered in thick, dense, glossy smears of

paint; Joaquin Mir y Trinxet’s intense veils of colour in Garden of Mogoda, 1915-19;

Emil Nolde’s slabs of deep blue, bright red, yellow and green forming a solid wall

of blooms in Flower Garden (O), 1922; and Gustav Klimt’s cascade of flowers in Cottage

Garden, 1905-07. Perhaps one of the oddest, yet most interesting, paintings is

Henri Matisse’s The Rose Marble Table, 1917: the salmony-pink, octagonal table,

stands against a predominantly brown ground relieved only by some dark green

foliage; on the table’s perspectivally tilted surface is a small basket and

three small green spheres of what might be fruit. The uncharacteristic gloom of

this picture, by a typically joyful painter, is ascribed to then ongoing

horrors of the Great War.

Finally,

however, the show belongs to Monet. Three rooms are devoted to his paintings.

In the first, situated in the middle of the exhibition, are paintings executed

from around 1895 to 1905: some of his much reproduced paintings of the Japanese

footbridge across the pond in his garden are so familiar that they seem like

clichés; however, the paintings of water lilies and swathes of blossom are seductively

subtle essays in colour and form. The other two rooms form the climax to the

exhibition and are simply stunning. In the first of these The Japanese Bridge

c1923-25 is a dense shimmer of deep, rich reds and greens dissolving the form

of the bridge so that it is only just perceptible.

The final

room is spectacular. On one side is the huge Water Lilies (after 1918) - a 4

metre-wide haze of pale yellow-greens within which occasional highlights of

orange-red flowers glow. And opposite is the truly immense triptych, Water

Lilies (Agapanthus), c1915-26, altogether some 12 metres wide: this stands not

just as the apotheosis of Monet’s career as a painter but is pregnant with the

then future possibilities of painting and abstraction. Magnificent.

Richard Salkeld.

(Click on images to enlarge.)

|

| Edouard Manet, Young Woman Among Flowers, 1879 |

|

| Gustav Klimt, Cottage Garden, 1905-07 |

|

| Emil Nolde, Large Poppies, 1908 |

|

| Emil Nolde, Flower Garden (O), 1922 |

|

Santiago Rusiñol, Glorieta VII, Aranjuez, 1919

|

|

| Joaquin Mir y Trinxet, The Artist's Garden, c1922 |

|

| Claude Monet, Water Lilies, after 1918 |

|

| Claude Monet, Water Lilies (Agapanthus), c1915-26 (detail) |

|

| Claude Monet, Water Lilies (Agapanthus), c1915-26 (installation view) |