If you want to be famous, you have to be worse at something than everyone else in the world. (Miroslav Tichý, quoted in Dyer, G. (2010) Working the Room, Edinburgh: Canongate, p74)

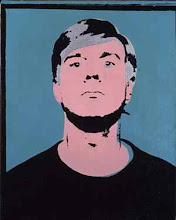

Miroslav Tichý died on 12th April at the age of 84. He was a 'primitivist' photographer who lived the life of a derelict and made his own cameras from scavenged junk. His voyeuristic pictures of women, taken in his home town in the Czech Republic were off-kilter, either over or under exposed, stained, bleached, scratched and... wonderful. See some examples, below.

I only 'discovered' Tichý last year, and almost all I know about him is gleaned from a wonderful essay by Geoff Dyer (Dyer, Geoff (2010) "Miroslav Tichy" in Working the Room: Essays and Reviews, 1999-2010, Edinburgh: Canongate, pp72-79). As Dyer records, Tichý only came to public attention in 2004 when Roman Buxbaum, who had begun collecting his work, wrote an article which led to an exhibition in Seville; in 2008 Tichý was given a show at the Pompidou Centre, Paris.

See also Roman Buxbaum on Miroslav Tichý, Miroslav Tichý: Tarzan Retired, by Roman Buxbaum, and Blog essay by Mark Power.

Sorry this comes a year and a half too late – I hadn't realised Tichý had died. There's a great filmed interview with him, I can't remember who by – I saw it in one of the two exhibitions of his work that I came across, I think the same one (Sydney Biennale 2008) that had some wonderful examples of his home-made cameras on show. While there's an unrepentant voyeur at large in Tichý, there's also a terrific uncompromising commitment to the freedom to do what he wanted to do, which in pre-1989 Czechoslovakia took a great deal more obstinate courage than in more recent times.

ReplyDeleteTichý took to the nth degree something that delighted me when I first saw Brancusi's photographs – his actual prints, I mean; these had all the signs of being done by hand, and a refusal of conventional craft values – they had stains on them, they accepted over and under-exposure and lack of perfect focus, they often had big fingerprints on them, and generally exuded a robustness of attitude to 'perfection' (the sculptor Brancusi had politely declined his friend Man Ray's invitation to introduce him to the man who made his prints – he knew how important it was to do it all himself).

Where Brancusi certainly knew the value of cultivating your own myth, Tichý genuinely seems to to have been the best kind of eccentric, wholly unconcerned with what anyone else thought of him. He'll live on.