I am very used to endless debates about ‘what is art?’, and, of course, ‘can a photograph be art?’ However, one might have thought that the question ‘what is photography?’, being medium specific, would be more straightforward. However, with the opening of this year’s Deutsche-Börse photography prize exhibition there are hints that the matter is not so simple; or, at least, in the view of Sean O’Hagan writing in the Guardian, who asks: ‘When is contemporary photography not photography?’

The shortlisted photographers for the Deutsche-Börse are: Thomas Demand, Elad Lassry, Roe Ethridge, and Jim Goldberg (see above and below for examples of their work); the exhibition has now opened at Ambika P3, and will continue until 30th April. The winner will be announced on 26th April.

As noted previously, in relation to the announcement of the shortlist, there have been some rumblings of discontent both about the prize itself and The Photographers’ Gallery, which organises it. (This year’s exhibition is temporarily accommodated at Ambika P3 while the Photographers’ Gallery is being extended).

Sean O’Hagan’s article reprises an argument he raised a few months ago (Do the Deutsche Börse prize jury really get photography?) and cites complaints made by photographers Chris Steele-Perkins, Brian Griffin and Nick Turpin and critic Francis Hodgson. (See BJP interview with Photographers’ Gallery director Brett Rogers for more details and quotes.)

O’Hagan’s specific argument is, first, that the Photographers’ Gallery and the Deutsche-Börse prize are too narrow in their focus, and second, that, so-called, conceptual photography may be art, but it isn’t proper photography.

O’Hagan suggests that the Deutsche-Börse should be re-branded as a conceptual photography prize, and even that The Photographers’ Gallery itself should be renamed! (Perhaps as ‘The Artists Who Use Photography Gallery’?)

With respect to the first point there may well be a case to answer that the Photographers’ Gallery is guilty of a bias towards a certain sort of practice – no such institution can be wholly neutral or even handed.

O’Hagan describes three out of the four shortlisted photographers as conceptual artists who deploy photography as part of their practice. The complaint, as I understand it, is not so much against ‘conceptual photography’, per se, but that the prize and the Photographers’ Gallery favour such work at the expense of straight photography, street photography, reportage, documentary, portraiture … This is reminiscent of the perennial complaint that the Turner Prize routinely marginalises painting in favour of installation and multi-media work. However, recent shortlists have included: Donovan Wylie (2010), Paul Graham (2009), John Davies (2008), Luc Delahaye (2005) all of whom might be thought to represent straight photography, street photography, reportage, documentary.

With respect to the second point, while it is perfectly clear that the work of, eg, Thomas Demand and, say, Chris Steele-Perkins is very different, it seems to me a little unfortunate to pigeon-hole the former as ‘conceptual’ and the latter as, by implication not – ie lacking in ideas or thought? Perhaps I am being a little pedantic here? - I do understand that ‘conceptual’ is being used here to connote a practice which is ‘non-traditional’ in so far as it eschews the ‘straight’ approach; but it seems a very back-handed compliment to Steele-Perkins, Griffin, Turpin, et al to suggest that their work lacks a conceptual dimension.

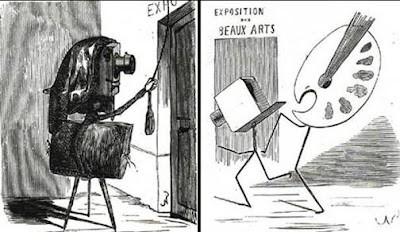

Given the history of photography’s relation to ‘art’ this complaint seems both odd and not a little ironic. The relationship of photography and art has been fraught for much of the medium’s existence; however, the admission of the photographer to the Salon seems now to have been well and truly established.

Nadar, left: Photography Asking for Just a Little Place in the Exhibition of Fine Arts, From Petit Journal pour Rire, 1855; right: The Ingratitude of Painting, Refusing the Smallest Place in its Exhibition, to Photography to whom it Owes so Much, From Le Journal Amusant, 1857

(Why, the Tate has even appointed, in 2009, its first curator of photography: Simon Baker, albeit 70 (yes, 70!) years later than MoMA, NY, whose first curator, Beaumont Newhall, literally ‘wrote the book’ on photography: The History of Photography.) We have come a long way since 1982, when Alan Bowness, the then director of the Tate, explained to Colin Osman that the Tate did not collect the work of photographers but did collect the work of artists who used photography: you have to be an artist and not only a photographer to have your work in the Tate (Brittain, David ed. (1999) Creative Camera: Thirty Years of Writing, Manchester: Manchester Univ. Pr., pp66-72). What is ironic is that the ‘artists’ in question were ‘conceptual artists’, but their use of photography was arguably ‘straight’, to a fault – eg Richard Long, Hamish Fulton, John Hilliard, the Bechers,et al. O’Hagan’s objection to Demand’s selection for the Deutsche-Börse seems to be that the amount of time and effort he expends in constructing the models he photographs, means that the process is all, and the end result simply a visual record of the end result. The implied conclusion being that while this may be art, it is not ‘proper photography’. In his earlier piece O’Hagan laments the Deutsche-Börse’s failure to find a place for photography without pretensions and wonders when photography will shed its postmodern pretensions. Perhaps when a new generation of curators replaces the current ones, many of whom seem to have been forcefed Baudrillard and the like at college and never quite recovered.

In taking this position he cites Paul Graham (Deutsche-Börse finalist, 2009) whose recent talk, “The Unreasonable Apple”, argued that:

there remains a sizeable part of the art world that simply does not get photography. They get artists who use photography to illustrate their ideas, installations, performances and concepts, who deploy the medium as one of a range of artistic strategies to complete their work. But photography for and of itself - photographs taken from the world as it is– are misunderstood as a collection of random observations and lucky moments, or muddled up with photojournalism, or tarred with a semi-derogatory ‘documentary’ tag.

But Graham’s argument, which does complain that ‘straight’ photographers

will almost never be considered for Documenta, or placed alongside other artists in a Biennale, or found for sale in major contemporary art galleries and art fairs, is, nevertheless, more nuanced than O’Hagan’s: Graham makes it clear that he has ‘zero problems’ with the work of eg, Thomas Demand, Cindy Sherman, Jeff Wall, et al – his point is that there is a lack of critics, curators, writers, who are able to articulate and take seriously the nature and value of photographs taken from the world as it is

and who can

understand the nature of the creative act when you dance with life itself - when you form the meaningless world into photographs, then form those photographs into a meaningful world.

This it seems to me is a fair point – it is not the ‘pretensions’ of Demand, Lassry, Ethridge, etc at issue, it is the pretensions of the critical discourse which surrounds them and the sheer difficulty of writing about photography. While it is true that O’Hagan, too, insists that Demand is an interesting artist, his rhetorical insistence that he is not a photographer simply muddies the water.

Roe Etheridge, Thanksgiving (Green Dress), 2009

No comments:

Post a Comment